Beyond the Playbook

Why Fund II Requires Fundamental Strategic Recalibration

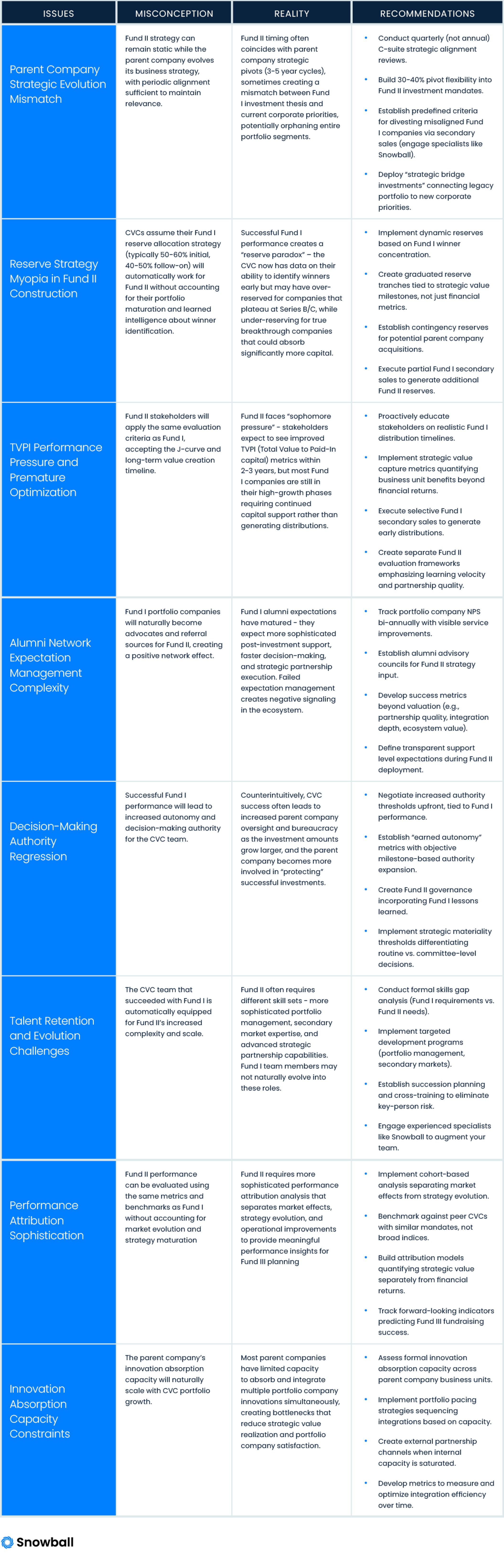

Corporate venture capital (CVC) teams approaching their second fund face a deceptive challenge: success with Fund I often breeds strategic complacency rather than operational evolution. Far more than representing simply capital deployment continuity, the transition from Fund I to Fund II constitutes a critical inflection point where institutional learning, portfolio maturation dynamics, and parent company strategic priorities converge to demand fundamental operational recalibration. Despite this reality, many CVC teams harbor eight persistent misconceptions that threaten Fund II performance and stakeholder confidence.

8 Misconceptions that Threaten Fund II

Strategic alignment assumptions, where teams believe Fund II strategy can remain static while parent companies undergo inevitable strategic pivots.

Reserve allocation approaches that fail to account for demonstrated winner- identification capabilities.

Performance evaluation frameworks that ignore the “sophomore pressure” phenomenon.

Alumni network management expectations that underestimate matured portfolio company requirements.

Decision-making authority dynamics where success paradoxically increases bureaucratic oversight.

Talent development gaps between Fund I operational capabilities and Fund II sophistication demands.

Performance attribution methodologies that conflate market effects with operational excellence.

Innovation absorption capacity constraints that create strategic value realization bottlenecks.

Parent Company Strategic Evolution Mismatch

Corporate venture capital teams commonly assume Fund I’s investment thesis will remain relevant for Fund II. This misconception stems from treating corporate strategy as static. In reality, Fund II timing typically coincides with the parent organization’s three-to-five-year strategic cycle refresh, creating misalignment where entire portfolio segments become strategically orphaned.

When Fund I companies fall outside evolved corporate priorities, they lose access to strategic resources, partnership opportunities, and internal advocacy that make corporate venture capital valuable. This dissatisfaction spreads through the entrepreneurial ecosystem, damaging the CVC’s reputation and making Fund II dealflow development significantly harder.

Addressing this requires implementing quarterly strategic alignment reviews directly with C-suite leadership rather than relying on annual check-ins. Annual reviews arrive too late; by the time a strategic pivot becomes apparent, the CVC may have already deployed significant capital in directions the company no longer values. Quarterly engagement creates an early warning system while there’s still time to course-correct. These should be working sessions where the CVC learns about emerging priorities before they’re publicly announced.

Complementing this cadence, CVCs should develop flexible investment mandates that explicitly permit pivoting 30-40% of Fund II focus areas based on corporate strategic evolution. This flexibility must be negotiated upfront. When stakeholders approve Fund II, they should explicitly acknowledge that strategic adaptation is expected, not a failure of the original thesis. This creates psychological permission for evolution rather than forcing the CVC to defend changes as corrections to flawed initial planning.

When strategic misalignment becomes irreparable, CVCs need predefined criteria for executing divestitures through secondary sales and other means. However, selling venture positions can be operationally complex, requiring sophisticated valuation analysis, buyer identification, negotiation expertise, and reputation management. Many CVC teams lack this specialized experience, which makes engagement with operating partners like Snowball essential.

Specialists bring operational expertise that maximizes value recovery while preserving market relationships, something critical when the ecosystem is watching how you treat companies that fall out of strategic favor.

Finally, consider deploying strategic bridge investments that connect legacy portfolio companies to emerging corporate focus areas. If the parent company shifts from cloud infrastructure to AI applications, for example, a bridge investment might back a company building AI development tools that integrate with both existing portfolio companies and the new strategic direction. This approach extends portfolio relevance, protects deployed capital, and demonstrates sophisticated portfolio management that looks beyond individual bets to ecosystem construction.

Reserve Strategy Myopia in Fund II Construction

Many CVC teams assume the standard 50-60% initial investment and 40-50% follow-on reserve ratio that worked for Fund I will automatically translate to Fund II. This ignores Fund I’d most valuable intelligence: empirical data about the team’s ability to identify winners early.

This creates what can be termed the reserve paradox. If Fund I demonstrated strong conviction-setting capabilities – identifying breakthrough companies early while other investors remained skeptical – then the historical split under-reserves for the team’s greatest strength. Conversely, the team may over- reserve for companies that plateau at modest valuations. The problem this creates compounds over time. Under-reserving for genuine winners means losing pro-rata rights precisely when companies achieve breakthrough traction, while over-reserving for plateau companies traps capital in uninspiring returns.

Implementing dynamic reserve allocation based on Fund I winner concentration analysis addresses this issue. If Fund I performance was driven by two or three clear winners while other investments delivered modest outcomes, Fund II could consider 70-30 or even more aggressive reserve ratios favoring follow-on deployment.

This isn’t about abandoning diversification but about honest assessment of where the team creates distinctive value. The analysis should examine not just which companies succeeded but when the CVC’s conviction diverged from broader market consensus. Those inflection points reveal where the team possesses genuine edge.

Developing graduated reserve tranches adds further sophistication. Rather than committing all follow-on capital based on traditional milestones like Series B qualification, this approach increases capital allocation to companies hitting specific strategic value milestones beyond purely financial metrics. These might include achieving enterprise deployment with the parent company, validating technology in production environments, or demonstratin ecosystem effects that benefit multiple portfolio companies. This captures the multidimensional value creation that CVC uniquely measures and ensures capital flows to companies delivering strategic value, not just those achieving conventional venture benchmarks.Creating contingency reserves specifically designated for companies approaching strategic acquisition by the parent company addresses another Fund II reality. When portfolio companies mature to acquisition consideration, the parent company often expects the CVC to participate in later funding rounds. Without dedicated reserves for this scenario, the CVC faces an uncomfortable choice: decline to participate and signal doubt about the pending acquisition, or scramble to find capital from reserves intended for other purposes.

Finally, proactively leveraging secondary markets to generate liquidity from Fund I positions converts unrealized gains into additional Fund II reserves. Traditional VCs routinely employ this capital recycling strategy, but CVCs often overlook it. Selling partial positions in appreciated companies—particularly those where strategic value has been captured but financial upside remains—generates immediate capital for Fund II winner backing.

TVPI Performance Pressure and Premature Optimization

CVC teams completing successful Fund I deployments often assume stakeholders understand venture capital’s long-term value creation timelines, leading to the misconception that Fund II will be evaluated using the same patient framework.

The reality proves less forgiving. Fund II faces “sophomore pressure” as stakeholders expect improved TVPI (Total Value to Paid-In Capital) metrics within 2-3 years, even though most Fund I portfolio companies remain in high-growth phases requiring continued capital support rather than generating distributions. Fund I was experimental, so patience came easily, but Fund II represents scaled commitment where stakeholders expect evidence of justified confidence. The problem intensifies when Fund I paper valuations look impressive but haven’t converted to realized returns, creating anxiety about whether marks reflect genuine value.

Failing to address this creates a damaging cycle. Stakeholders become skeptical about Fund II resource allocation, questioning whether continued investment makes sense when Fund I hasn’t “proven itself” through distributions. This skepticism manifests in slowed decision- making, reduced follow-on capital approval, and premature pressure to force exits. The CVC team finds itself defending the program’s existence rather than focusing on value creation.

Proactive stakeholder education on Fund I portfolio maturation curves and realistic distribution timing addresses this directly. CVC teams should present detailed cohort analysis showing how long comparable VC funds took to generate distributions, overlaid with Fund I’d specific portfolio composition and expected exit timelines. This education should happen beforeFund II approval, resetting expectations about when distributions will materialize.

Implementing strategic value capture measurement systems provides a crucial alternative performance narrative. These systems quantify tangible business unit benefits from Fund I investments beyond financial returns – e.g., technology adoption metrics, partnership revenue generated, talent acquisition statistics, and competitive intelligence value. When stakeholders see that Fund I delivered $50M in measurable strategic value even before distributions, their patience for financial returns increases substantially. This reframes the investment from “expensive experiment with unclear returns” to “delivering value through multiple channels.”

CVC teams could also consider executing partial secondary sales of appreciated Fund I positions to generate early distributions. While this means selling portions of winning positions before maximum value realization, the psychological reassurance to stakeholders proves valuable. This approach requires careful position selection; selling small stakes in winners where strategic value has been captured but significant financial upside remains allows the CVC to maintain material exposure while demonstrating capital discipline.

Establishing separate evaluation frameworks for Fund II that emphasize strategic learning velocity, partnership quality metrics, and

innovation pipeline development during early deployment years creates performance narratives that transcend simple TVPI comparisons. These frameworks acknowledge that Fund II’s first 2-3 years should be judged on deployment quality, ecosystem relationship building, and strategic positioning rather than financial returns that can’t yet materialize. By agreeing to these alternative metrics upfront, the CVC establishes legitimate performance benchmarks that demonstrate progress without requiring impossible early-stage distributions.

Alumni Network Expectation Management Complexity

Some CVC teams assume their Fund I portfolio companies will naturally evolve into enthusiastic advocates who refer high-quality dealflow. This assumption treats portfolio company relationships as naturally appreciating assets requiring minimal maintenance.

The reality reveals more complexity. Fund I alumni expectations likely will have matured significantly from their initial investment stage. When these companies were early-stage startups desperate for capital, basic introductions and standard board participation met expectations. Now, as established growth companies with multiple sophisticated investors, they anticipate refined post-investment support infrastructure, accelerated decision-making on follow-on funding, and proactive strategic partnership execution beyond introductory emails.

When CVCs fail to meet these evolved expectations – for instance, continuing to provide Series A-level support to Series C companies with Series C-level needs – dissatisfaction develops and propagates through the entrepreneurial ecosystem far faster than positive referrals, making Fund II dealflow development significantly harder.

Implementing formal portfolio company feedback collection cycles creates systematic early warning systems for relationship deterioration, which can surface concerns while they’re still addressable. Critically, this tracking must lead to action, as collecting feedback without visible service improvements generates even more frustration by demonstrating the CVC hears concerns but doesn’t respond.

Establishing alumni advisory councils transforms portfolio companies from passive beneficiaries into active program architects. These councils provide structured input on Fund II investment criteria (e.g., What sectors or stage focus would complement existing portfolios?), portfolio support service design (e.g., What resources would accelerate growth most?), and ecosystem development (e.g.,

What connections or partnerships would create mutual value?), creating psychological ownership of Fund II’s success while generating strategic insights. Developing comprehensive portfolio company success metrics extending beyond valuation appreciation demonstrates genuine commitment to portfolio success rather than transactional capital deployment. These metrics measure:

Strategic partnership quality – How many revenue-generating partnerships were facilitated?

Parent company integration depth – How extensively is the portfolio company’s technology deployed internally?

Ecosystem value creation – How has the portfolio company benefited from connections to other portfolio companies?

When the CVC team reports these metrics in board meetings and annual reviews, it signals that success is defined multidimensionally. Portfolio companies notice this difference and respond with increased loyalty and advocacy.

Finally, creating transparent communication protocols explicitly defining ongoing support levels Fund I companies can expect during Fund II’s active deployment phase manages expectations proactively rather than reactively addressing disappointment. This requires honest conversations about what they can reliably expect and what they need to drive independently, preventing resentment when attention naturally shifts toward newer investments requiring intensive early-stage support.

Decision-Making Authority Regression

One of venture capital’s most counterintuitive dynamics is that successful performance often leads to increased oversight rather than expanded autonomy. CVC teams naturally assume Fund I success will translate to greater decision-making authority for Fund II. This misconception stems from underestimating organizational risk psychology and political dynamics as programs scale.

The reality reveals “success-driven bureaucracy.” As Fund I investments mature and valuations appreciate, parent company executives who previously paid little attention to the CVC program suddenly take keen interest. Board-level discussions about multi-million- dollar positions trigger executive concern about protecting valuable assets, manifesting in expanded approval requirements, additional committee reviews, increased documentation demands, and slower decision cycles.

This creates real competitive disadvantage. When hot deals require investment decisions within 48-72 hours, a CVC requiring two weeks of internal approvals simply can’t compete. Over time, lead investors stop including the CVC in competitive rounds, and the CVC’s decision velocity reputation deteriorates.

Proactively negotiating increased investment authority thresholds explicitly tied to Fund I performance metrics prevents this regression by codifying autonomy expansion before Fund II deployment begins. This negotiation should happen during Fund II approval discussions: “Given Fund I’s X% IRR and Y% strategic value delivery, we propose increasing individual investment authority from $5M to $10M without executive committee approval.” By framing expanded authority as the earned consequence of demonstrated performance rather than a separate request, the CVC transforms what might be seen as empire-building into logical organizational evolution. The key is securing this commitment in writing as part of Fund II’s governing documents, not relying on informal understanding that evaporates when organizational leadership changes.

Establishing earned autonomy frameworks provides even more sophisticated governance evolution. These frameworks clearly define decision-making authority expansion tied to verifiable performance milestones. For example, when Fund II reaches 1.5x TVPI, authority increases to $15M investments without approval. This creates a transparent, objective system where autonomy expands based on demonstrated value creation rather than subjective judgment.Creating distinct governance structures for Fund II that formally incorporate Fund I operational lessons also prevents repeating dysfunction while maintaining appropriate oversight. This requires honest retrospective analysis:

What approval processes created unnecessary friction in Fund I without adding value?

Where did committee review improve decision quality versus simply adding delay?

Which decisions benefited from broad stakeholder input versus those where expert judgment sufficed?

Document these findings and present them as proposed Fund II governance improvements.

Implementing strategic materiality thresholds provides the most practical operational solution. These thresholds differentiate routine investment decisions (which the CVC team handles autonomously) from strategically material commitments (requiring parent company input). For example, initial investments under $8M and follow-on investments under $12M proceed with CVC Managing Director approval; investments exceeding these thresholds, investments in new strategic domains, or investments creating potential conflicts require Investment Committee approval. The specific thresholds matter less than establishing clear, objective criteria preventing the default of seeking approval for every decision.

Talent Retention and Evolution Challenges

The assumption that the CVC team successfully executing Fund I automatically possesses requisite capabilities for Fund II’s demands represents perhaps the most dangerous misconception because it directly impacts execution quality.

The reality is that Fund II often demands qualitatively different competencies beyond Fund I’s skill requirements. Fund II operations involve sophisticated portfolio management across dual-fund structures, secondary market transaction expertise, advanced strategic partnership structuring, and institutional- grade performance analytics. These aren’t just refinements of Fund I capabilities, but genuinely new competency domains rarely required during initial fund deployment but critical for mature fund management.

Failing to address these capability gaps can create escalating problems. Portfolio companies receive suboptimal support, secondary sale opportunities go unexplored, performance reporting remains unsophisticated, and team members feel increasingly overwhelmed, leading to frustration, burnout, and potentially departure. Meanwhile, stakeholders grow concerned as operational execution quality fails to match the program’s expanded scale and complexity.

Beginning with formal skills gap analysis comparing Fund I operational requirements against Fund II anticipated demands identifies specific capability deficits requiring development or recruitment. This analysis should be detailed and honest, examining not just whether the team can perform required tasks but whether they can execute them at the sophistication level Fund II demands. The gap analysis should produce specific, actionable findings.

Implementing professional development programs specifically targeting advanced portfolio management techniques and secondary market mechanics addresses identified gaps through upskilling where feasible. This isn’t generic executive education but targeted capability building. Partner with Snowball to provide hands-on training in secondary transaction mechanics, valuation methodology, and buyer identification, or to develop sophisticated tracking systems and value-add frameworks. Send team members to advanced programs focused on corporate- startup partnership structuring. This investment in human capital development demonstrates commitment to team growth while building necessary capabilities.

Consider adding specialized roles addressing Fund II’s distinct operational demands when skill gaps exceed what development programs can bridge. These might include:

Specialists, like Snowball, who understand secondaries transaction mechanics, buyer networks, and valuation analysis,

Strategic partnership managers focused exclusively on corporate integration rather than dealmaking, providing dedicated capacity for portfolio company support,

Advanced due diligence professionals capable of sophisticated technical assessment as investment stages mature and technical complexity increases.

Adding these roles isn’t an admission of Fund I team inadequacy, but rather a recognition that scaled operations require specialized expertise that generalist investors shouldn’t be expected to possess.

Finally, establishing succession planning and cross-training protocols for key CVC team positions eliminates key-person risk. Cross-training ensures that at least two team members can perform each critical function. Succession planning identifies development paths for junior team members to grow into senior roles and contingency plans if senior members depart. This institutional knowledge preservation proves especially vital during Fund II deployment when losing key team members would severely impact both portfolio support quality and new investment capability.

Performance Attribution Sophistication

The belief that Fund II performance can be evaluated using identical metrics andbenchmarks as Fund I can reflect analytical inadequacy that obscures genuine performance insights needed for Fund III planning. This misconception treats performance measurement as static.

The reality demands more sophisticated performance attribution frameworks that decompose returns into constituent sources:

Market vintage effects – benefiting or hindering all investors in specific deployment periods regardless of skill,

Strategy evolution contributions – improved returns from refined investment criteria and focus area adjustments, and

Operational excellence components – value-add capabilities enhancing portfolio company outcomes beyond pure capital provision). Without this decomposition, it’s difficult to determine whether Fund II outperformance resulted from riding a favorable venture market, from improved investment strategy, or from genuine operational excellence. This matters enormously for Fund III planning, as blindly replicating Fund II approaches without understanding what actually drove results risks strategic misdirection.

The problem compounds during Fund III discussions. If Fund II performance is attributed entirely to skill when favorable markets actually drove much of the return, Fund III will disappoint when markets normalize. Conversely, if the team genuinely improved operational capabilities but this gets obscured by overall market metrics, stakeholders undervalue legitimate progress.

Implementing cohort-based performance analysis explicitly accounting for market vintage effects and strategy evolution enables fair comparison between Fund I and Fund II despite different deployment contexts. This involves analyzing how peer CVCs and traditional VCs deploying capital in the same vintage periods performed, isolating market effects from Fund II- specific factors.

If Fund II achieved 25% IRR while the vintage average was 28%, that actually represents underperformance despite the respectable absolute number.

Conversely, if Fund II achieved 18% IRR when the vintage average was 12%, that demonstrates genuine outperformance despite modest absolute returns.

The analysis should also track how strategy evolution impacted results. If Fund II shifted 40% of focus from enterprise software to AI infrastructure, how did that reallocation affect returns compared to maintaining Fund I’s focus?

Developing internal benchmarking systems tracking performance against peer CVCs with similar strategic mandates provides more relevant comparison than broad venture market indices. Comparing a CVC focused on supply chain innovation against the Cambridge Associates VC Index, which includes consumer internet and biotech, obscures more than itreveals. Instead, teams should identify 5-8 peer CVCs with similar sector focus and track comparative performance across multiple dimensions: investment pace, average check size, follow-on participation rates, portfolio company growth metrics, exit multiples, and strategic value delivery indicators.

Creating performance attribution models that explicitly separate financial returns from strategic value creation recognizes that a $5M investment generating $3M in financial returns plus $20M in strategic partnership revenue represents dramatically different value than pure financial metrics suggest. These models should quantify strategic value across multiple dimensions:

Revenue generated through portfolio company partnerships,

Cost savings from technology adoption,

Competitive intelligence value from market

insight access,

Talent pipeline value from portfolio company

recruiting relationships, and

Ecosystem effects from cross-portfolio synergies.

When stakeholders see that Fund II generated 1.8x TVPI plus $75M in strategic value, the program’s contribution becomes undeniable even if pure financial returns appear modest.

Establishing forward-looking performance indicators predicting Fund III fundraising success based on Fund II operational metrics creates leading rather than purely lagging assessment.

These indicators include:

LP perception scores from external venture capital limited partners who observe the CVC’s market reputation,

Portfolio company satisfaction metrics from NPS tracking systems,

Parent company strategic value delivery trends showing whether business unit integration is accelerating or stagnating, and

Ecosystem reputation signals from deal flow quality and co-investor interest.

By tracking leading indicators throughout Fund II deployment, the team can proactively address emerging concerns before they threaten Fund III viability.

Innovation Absorption Capacity Constraints

Perhaps the most overlooked misconception assumes the parent company’s capacity to absorb and integrate portfolio company innovations will naturally scale proportionally with CVC portfolio growth. This assumption reflects linear thinking, that if the parent company successfully integrated three portfolio company technologies during Fund I, surely it can integrate six technologies during Fund II when the portfolio doubles.

The reality proves that most parent organizations possess finite innovation absorption bandwidth governed by change management capacity, technology integration resources, business unit political dynamics,and executive attention constraints. Integration requires change management, stakeholder alignment, process redesign, and sustained executive sponsorship. As the CVC portfolio grows, multiple portfolio companies could simultaneously vie for integration attention, creating bottlenecks that reduce strategic value realization and portfolio company satisfaction.

The problem intensifies because innovation absorption capacity doesn’t improve automatically. Unlike manufacturing capacity that can be expanded through capital investment, innovation absorption depends on organizational change capability, a cultural competency that develops slowly and often remains static in large organizations optimized for operational efficiency.

Conducting formal innovation absorption capacity assessment across parent company business units quantifies realistic integration bandwidth before it becomes a constraining factor. This assessment examines multiple dimensions:

How many simultaneous integration initiatives can each business unit effectively manage?

What resources (technical, financial, human) does each integration require?

What political dynamics or competing priorities might impede adoption?

Which executives champion innovation integration versus those who resist additional complexity?

The assessment should produce specific capacity metrics that inform realistic portfolio construction and pacing.

Implementing portfolio pacing strategies deliberately sequences integration opportunities based on assessed parent company capacity rather than attempting simultaneous integrations that overwhelm organizational change capabilities. This might mean staging portfolio company partnerships across fiscal quarters, preventing a scenario where the CVC introduces multiple portfolio companies simultaneously to a business unit that then engages with none effectively.

Creating external partnership channels for portfolio companies when internal integration capacity reaches saturation ensures these companies can realize growth trajectories. This demonstrates sophisticated portfolio management that prioritizes portfolio company success over narrow internal-integration metrics. If the parent company lacks bandwidth to integrate a portfolio company’s technology but a strategic partner in the parent’s ecosystem has immediate need and capacity, facilitating that external partnership preserves the relationship and enables portfolio company growth.

Developing metrics measuring and optimizing parent company innovation integration efficiency over time treats absorption capacity as a developable organizational capability rather than a fixed constraint. These metrics track:

Integration cycle times - How long from concept approval to production deployment?

Resource requirements - How much time from which functions does each integration require?

Success rates - What percentage of approved integrations achieve full deployment?

Value realization timelines - How quickly do integrations generate measurable business impact?

By measuring these dimensions and identifying improvement opportunities, the CVC can work with corporate leadership to progressively expand bandwidth through process refinement, dedicated integration resources, or organizational structure changes.

Conclusion

The transition from Fund I to Fund II constitutes a strategic inflection point where accumulated learning, demonstrated capabilities, and evolved organizational contexts converge to demand fundamental operational recalibration. CVCs that treat Fund II merely as “more of the same” squander the institutional intelligence while failing to position themselves for the sophisticated portfolio management, strategic partnership execution, and performance demonstration that stakeholders increasingly demand.

The eight misconceptions outlined here privilege operational momentum over strategic evolution, assuming yesterday’s approaches will suffice for tomorrow’s challenges. Success with Fund I creates both opportunity and obligation to evolve fundamentally, implementing more sophisticated reserve strategies, governance frameworks that balance autonomy with appropriate oversight, talent configurations that match scaled operational demands, and performance measurement systems that reveal genuine value creation.

Those CVCs that embrace Fund II as an opportunity for strategic repositioning rather than operational continuation discover something profound: the same innovation-driven growth they seek to catalyze in portfolio companies applies equally to their own institutional evolution. Fund II done correctly can transform the CVC function into an enduring strategic capability that compounds value across multiple fund cycles.

The ultimate insight is that Fund II represents a critical choice point. CVCs can treat it as Fund I at larger scale, replicating established patterns while hoping for incrementally better results. Or they can recognize Fund II as the organizational maturation milestone it actually represents, using it to institutionalize learned lessons, eliminate structural constraints that limited Fund I effectiveness, and position both the CVC team and the parent organization for sustained innovation leadership. Those choosing evolution over repetition will find that Fund II becomes not just a capital deployment vehicle but a catalyst for organizational transformation that delivers compounding returns far beyond any individual investment’s financial outcome.