The Hidden Physics of Startup M&A Integration

Why Traditional M&A Playbooks Can Fail When Acquiring Technology Startups

Corporate development teams have spent decades refining the art of integrating mature businesses. The playbook is well-established: eliminate redundancies, consolidate operations, and extract cost synergies. However, the results are often disastrous when these same methodologies are applied to technology startup acquisitions. The acquired startup’s value evaporates within months, key talent departs, and the strategic rationale that justified a premium valuation becomes a cautionary tale.

The distinction is fundamental. Traditionally, and especially with mature acquisition target companies, mergers are often “scale deals” that create value through consolidation and elimination. In contrast, startup acquisitions are often “capability deals” that derive their worth from preserving the fragile ecosystem that generated innovation in the first place. The acquirer is not purchasing assets to be absorbed but rather acquiring a living system that likely operates on entirely different principles than the corporate parent.

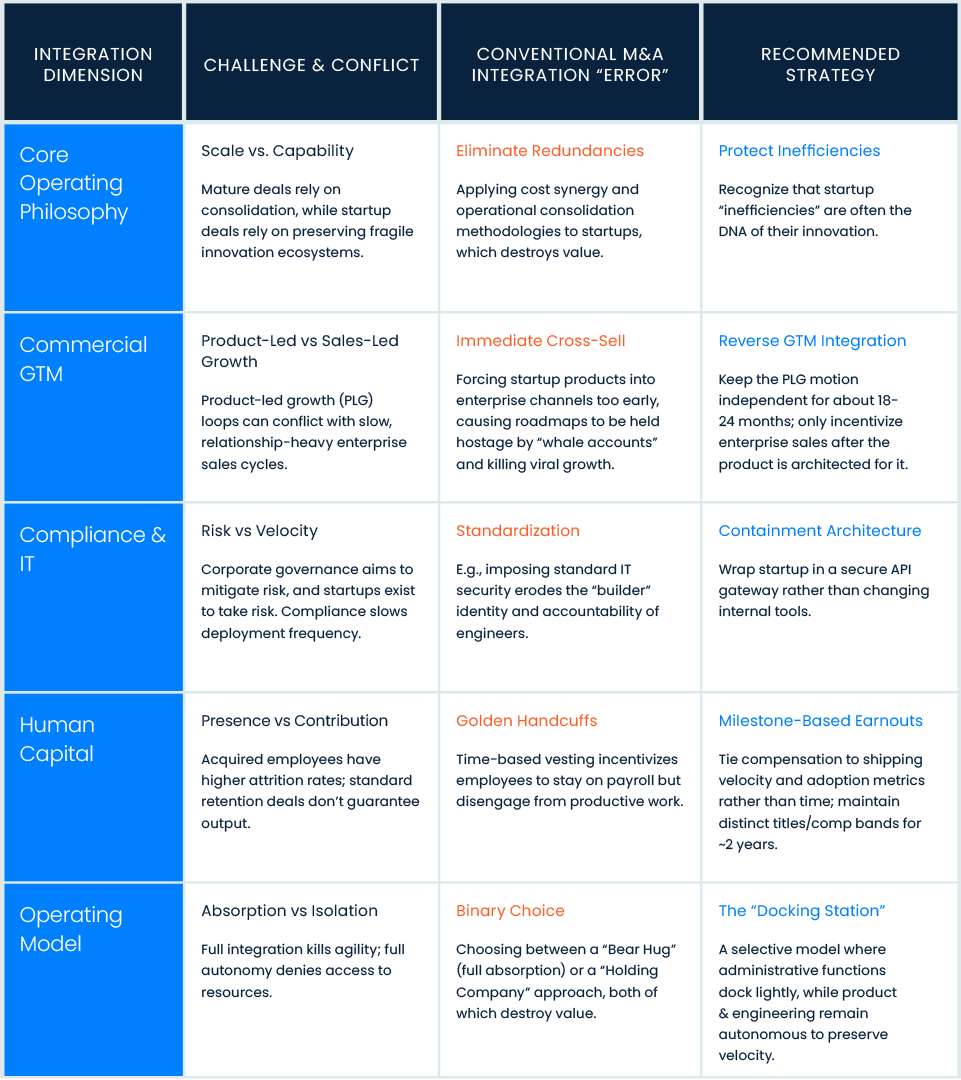

This article identifies four critical dimensions where startup integration diverges materially from conventional M&A integration and actionable recommendations that integration leaders can implement:

Commercial Go-To-Market (GTM) Architecture

Technology startups often employ product-led growth models that conflict fundamentally with enterprise sales motions, and forcing startup products into enterprise channels destroys the viral adoption loops that created value. Product-led growth motions of startups should be protected from enterprise sales-led motions for 18-24 months.Regulatory and Compliance Overhead

Corporate governance frameworks that are individually reasonable can collectively eliminate the operational velocity that constitutes a startup’s primary competitive advantage. Containment architecture that allows startups to maintain operational velocity while satisfying corporate governance requirements should be implemented.Human Capital Retention Dynamics

Employees acquired through startup acquisitions exhibit significantly higher attrition rates than standard hires, and conventional retention packages often incentivize presence rather than productive contribution. Retention packages should be structured around milestone-based earnouts tied to shipping velocity rather than time-based vesting.Integration Model Selection

The binary choice between full absorption and complete autonomy destroys value in different ways, and both extremes should be avoided. A “docking station” integration model that calibrates functional absorption to value preservation rather than operational convenience should be adopted.

Commercial GTM Mismatch: Product-Led vs Sales-Led Growth You Can Expect from Snowball

The collision between a startup’s product-led growth (PLG) motion and the acquirer’s sales-led engine is a challenge that can be most consequential to integration success. Technology startups increasingly rely on PLG models where customers discover, evaluate, and adopt products through self-service mechanisms. Sales cycles are measured in minutes, customer acquisition costs approach zero, and conversion is driven by product experience rather than relationship management. The enterprise acquirer, conversely, operates a fundamentally different commercial architecture: months-long procurement cycles, committee-based purchasing decisions, relationship-intensive account management, and pricing opacity that requires human negotiation.

The first-order integration instinct is to cross-sell the startup’s product to the acquirer’s Global 2000 client base, but this initiates a cascade of second and third-order effects that systematically destroy value. Enterprise sales representatives, compensated on quota retirement, rationally ignore small-ticket startup leads that consume time without moving numbers, and the startup’s viral growth loop gradually starves.

Product roadmaps start to become hostage to enterprise requirements, like single sing-on integrations, custom data residency, or on-prem deployment options. Engineering resources shift from core innovation to checklist features demanded by a handful of “whale accounts.” The self-service experience that drove organic growth can degrade as pricing pages redirect to “Contact Sales” gates. In this way, the very characteristics that made the startup attractive – speed, simplicity, viral adoption – can be systematically eliminated by well-intentioned integration efforts.

Recommendation

Implement a “reverse go-to-market integration” that protects the startup’s PLG motion as an independent commercial entity for a minimum of 18 to 24 months. The startup should continue acquiring and serving customers through its existing channels while the corporate parent separately develops an enterprise-packaged version. Enterprise sales should be incentivized to sell only after the product has been explicitly architected for enterprise consumption, not by forcing the raw product into inappropriate channels. The startup’s product roadmap must remain insulated from individual enterprise customer demands during this period.

Compliance Tax and Innovation Velocity

Large enterprises exist fundamentally to mitigate risk. Startups exist fundamentally to take it. When these opposing orientations collide during integration, the casualty is typically speed, which is the primary competitive advantage of the acquired company. Corporate information security and legal teams, fulfilling their legitimate mandates, impose standard governance frameworks – e.g., administrator access removed from engineer laptops, multi-stage CI/CD approval gates, mandatory workflow documentation in enterprise ticketing systems. Each requirement is individually reasonable, but collectively, they can be lethal to startup velocity.

The mechanical effects can become measurable, as deployment frequencies that once occurred daily migrate to weekly release windows. Engineers who fixed production issues in real-time might now submit change requests and wait for approval cycles.

But the deeper challenge is psychological. In a startup environment, engineers maintain personal ownership of system reliability. They respond to incidents at 2 AM because they are responsible for uptime. Many corporate compliance frameworks can shift this agency to “the process.” When engineers cannot access production systems, they cannot feel personally accountable for production outcomes. The “builder” identity that attracted top talent erodes, innovation velocity drops, and the engineers who possess the most options (precisely those the acquirer most needs to retain) might depart for environments where they can actually build.

Recommendation

Deploy “containment architecture” that satisfies corporate security requirements without constraining startup operations. Rather than forcing the startup to comply with enterprise IT standards, treat the startup environment as an untrusted network under a zero-trust security model. The startup retains its existing development tools, deployment processes, and access controls. The corporate parent could wrap the startup’s entire technical environment in a secure API gateway that provides monitoring, authentication, and data protection at the boundary. The startup keeps its fast tools, and the corporate acquirer gets its security controls. Both objectives are achieved without destroying the operational model that created value.

Human Capital Dynamics: The Startup Affinity Cliff

In capability deals, retention is the primary success metric. Research from MIT Sloan indicates that employees acquired through startup acquisitions exhibit significantly higher attrition rates than standard corporate hires, with approximately one-third departing within the first year.1

The attrition pattern follows a predictable trajectory: a honeymoon period immediately post-close, a “culture shock” cliff at twelve months as founders and early employees encounter corporate reporting structures, an acceleration of departures at twenty-four months when initial equity tranches vest, and eventual stabilization as remaining employees either fully assimilate or adopt a “rest and vest” posture.

Standard retention approaches often exacerbate rather than resolve these dynamics. Large retention packages denominated in restricted stock units create “golden handcuffs” that incentivize physical presence rather than productive contribution. Founders and key engineers remain on payroll but disengage from meaningful work, effectively representing sunk cost rather than active capability.

Worse, the visible compensation differential between acquired employees and existing corporate staff (where acquired “kids” earn multiples of legacy employee salaries for apparently less demanding work) can generate resentment that degrades productivity across the entire division. The acquirer pays premium compensation for declining contribution while simultaneously damaging the morale of its existing workforce.

Recommendation

Replace time-based vesting with milestone-based earnouts tied to shipping velocity and product adoption metrics rather than financial outcomes. Compensation should accelerate when the acquired team demonstrates continued innovation through rapid iteration, feature releases, and user growth. Compensation should decelerate when velocity declines.

Additionally, allow the startup to maintain its distinct title hierarchy and compensation bands for a defined transition period of approximately two years. This isolation prevents the “envy factor” from contaminating the broader organization while preserving the startup’s internal coherence. The objective is retention of productive contribution, not merely physical presence.

Strategic Synthesis: The “Docking Station” Integration Model

The most prevalent integration error is treating absorption as binary: either the startup is fully integrated into corporate operations, or it operates as a completely standalone subsidiary. Both extremes destroy value.

Full integration (the “bear hug” approach where HR, IT, finance, and sales are immediately absorbed) systematically eliminates the operational characteristics that generated the startup’s value. Within twelve months, the acquired company is indistinguishable from any other corporate division, and the premium paid represents pure value destruction. Complete autonomy (the “holding company” approach) severs the startup from the strategic resources that justified the acquisition. Without access to corporate distribution channels, customer relationships, or capital, the startup drifts without direction and eventually atrophies.

Sophisticated acquirers instead implement what might be termed a “docking station” model, calibrating integration intensity by functional domain based on value preservation requirements.

Administrative functions like finance and legal might achieve light integration, with the startup adopting the parent company’s general ledger coding and compliance frameworks while retaining operational autonomy. Go-to-market functions might employ a channel overlay structure, with corporate sales teams providing introductions and relationship access, but the startup’s sales organization closing deals and managing customer relationships. Product and engineering functions might maintain zero integration, with the startup preserving its technology stack, development tools, workflow systems, and deployment processes entirely independent of corporate IT.

The startup can connect to corporate resources where synergies exist without surrendering the operational independence that enables velocity.

Recommendation

When integrating a mature company, the integration leader’s mandate is to identify and capture efficiencies. When integrating a technology startup to preserve its innovation velocity, the mandate must invert and the integration leader must protect inefficiencies.

The “inefficient” practices that characterize startups (e.g., over-investment in engineering talent, disregard for expense policy constraints, deploying code without committee approval, etc.) are the operational characteristics that generated the value the acquirer paid a premium to access. If the goal is to preserve the innovation velocity of the acquired startup, then the integration function’s role is not to “fix” these practices but to insulate them from corporate antibodies while enabling selective access to corporate resources. The measure of integration success, in that case, should not just be operational consolidation.

Conclusion

The failure modes in startup M&A integration are rarely failures of intention. They are failures of recognition. Integration teams apply frameworks developed for fundamentally different transaction types to contexts where those frameworks systematically destroy value.

Cost synergies, the primary value lever in traditional M&A, are largely irrelevant in capability deals. Operational consolidation, the standard integration objective, can actively undermine the innovation systems that justify acquisition premiums. Compliance standardization, the corporate governance imperative, can eliminate the velocity advantages that made the startup strategically valuable.

Integration professionals confronting startup acquisitions must fundamentally reorient their approach. Oftentimes, the startup’s apparent “inefficiencies” can be features, not bugs. They represent the operational DNA that enabled innovation the acquirer could not replicate internally. The executives who master this reorientation will capture the strategic value that motivated the transaction. Those who apply traditional playbooks will reliably destroy it. The distinction between outcomes is categorical, not simply a matter of degree.

Author

Anthony Herman is Senior Advisor and Managing Partner of Snowball Innovation Advisory. With more than 15 years of experience as a venture capital investor, startup founder, and global corporate executive, Anthony helps organizations achieve sustainable, innovation-driven growth. He is based in Seattle, USA.